A lot has happened since Dec. 12, 2015, when the Paris Agreement was adopted by consensus of the 195 countries present at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21)–and more than what might have been expected. For starters, the agreement smoothly slid into force on Nov. 4, in record time for a document of this significance. This is a clear indication by governments to business and the financial markets that a low-carbon future is firmly on the agenda. Over the past year, the green bond market, a bellwether for climate finance, has grown at an impressive rate. Plus the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), launched on Dec. 4, 2015, is on target to deliver its recommendations to the Financial Stability Board (FSB) on Nov. 17 and a 60-day public consultation will commence in early December. Furthermore, at this year’s UN climate change summit (COP22) starting in Marrakech this week, we expect participants to flesh out a roadmap for further scaling up climate finance. However, in the area of green infrastructure investment in particular, S&P Global Ratings believes there’s still much to be done to meet the Paris Agreement’s targets. (Watch the related CreditMatters TV segment titled « Green Finance: Meeting The Climate Challenge, » dated Nov. 11, 2016.)

Overview

- Since its signing late last year, the Paris Agreement on climate change rapidly slid into force on Nov. 4, a clear indication to business and the financial markets that a low-carbon future is firmly on the agenda.

- The green bond market grew at an impressive rate in the past year, with 2016 issuance already up 50% on last year’s total, though more could be done to expand the market.

- At the UN climate change summit in Marrakesh starting this week, in the area of climate finance, participants will turn to the practical tasks of developing voluntary, consistent disclosures of pledges and requirements; and finalizing a plan to mobilize the $100 billion a year in flows to developing countries for climate change adaptation and mitigation.

- S&P Global Ratings believes that trends in green infrastructure investment show the need for a significant scaling up of both public- and private-sector capital flows to meet the 2-degree target.

The Paris Agreement reached at COP21 on Dec. 12, 2015, was a momentous signal to the world that the tides are changing on climate policy (see « Paris Agreement–A New Dawn For Tackling Climate Change, Or More Of The Same » published on RatingsDirect on Jan. 18, 2016). The common framework committed all countries to submit their « best effort » emissions reduction plans, which they are to revise upward every five years via a ramping-up mechanism. Parties have also agreed to report regularly on their emissions and implementation efforts, and undergo international review. The agreement set out a number of ambitious targets. Here, S&P Global Ratings outlines a few of those targets that, in our opinion, are potentially most relevant to the green finance sector:

- Carbon neutrality, which means that emissions from carbon sources must equal those absorbed by carbon sinks (such as forests that take up carbon dioxide) so that no net emissions will be added to the atmosphere, to be reached during the second half of this century.

- Mobilizing $100 billion a year in climate change support by 2020 (both mitigation and adaptation) through to 2025, after which a more ambitious target will be set.

- Making finance flows consistent with a pathway toward low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development

- Reaffirming the 2-degree Celsius goal while urging efforts to limit warming to 1.5 degrees, which sends a signal to heavy emitting industries that governments are serious about emissions reduction.

The Surging Green Bond Market

Issuance to date for 2016 (as of Nov. 1) stands at $64.3 billion, which is already 1.5 times total issuance in 2015 of $42 billion. We are observing a diversification in the market as proceeds are used for increasingly different types of projects. The dominance of renewable energy is starting to decline, and we are seeing an increase in water, waste, and adaptation-focused bonds. This should help to spur the market further as new corporate and municipal issuers are drawn to the space.

Another notable milestone this year has been the announcement by a number of sovereigns that they will issue their first green bonds. It looks like France will be the first to issue in 2017, with a proposed initial €3 billion of green bond issuance for a total of €9 billion through 2019. France’s could be the first of many sovereign green bonds to come to market as governments begin to source the financing required to enable them to meet their COP21 pledges, known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs).

As issuer and project types diversify in this market, there is a need for comparability and environmental analysis behind the « green » label. S&P Global Ratings is looking into this niche, with plans to potentially release a Green Bond Evaluation product that provides an independent view of transparency and governance surrounding the use of the bond’s proceeds and also proposes to go further by evaluating the expected environmental impact of the bond. This analysis aims to offer the market a methodology for assessing the environmental impact of different bonds, for example, a water-focused green bond compared with an industrial efficiency focused green bond (see « Proposal For A Green Bond Evaluation Tool, » published on Sept. 2, 2016).

Identifying other needs, Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England and FSB chairman, suggested in a speech on Sept. 22 in Berlin that the following measures could enable further growth in the green bond market:

- The development of a « term sheet » of internationally recognized standardized terms and conditions for a green bond;

- Creation of voluntary definitional frameworks, certification, and validation to give certainty to issuers and investors that the project being financed is green;

- Integration of environmental risk and green certification into credit ratings;

- Development of green bond indices to unlock the potential investment power of passively managed investments; and

- Assessment of the scope for standardization and harmonization of principles for green bond listings to promote efficient trading and adequate liquidity.

S&P Global Ratings already examines climate and environmental risk as part of its ratings process, which we explain in « How Environmental And Climate Risks Factor Into Global Corporate Ratings, » published on Oct. 21, 2015, and we plan to expand our work in this area outside credit ratings to include green bond evaluations.

The TCFD: Tools For Green Investment

The FSB task force’s mission is to develop recommendations for voluntary, consistent climate-related financial risk disclosures that companies use to provide information to lenders, insurers, investors, and other stakeholders. Despite the voluntary nature of the group’s recommendations, most large corporates in Group of Twenty countries, and potentially others, are expected to adopt the recommendations over time.

The recommendations are expected to standardize the plethora of current reporting systems making disclosures more comparable and therefore useful to investors. As well as providing metrics and targets for more conventional historical emissions performance, they are also expected to go further to examine future risks, by recommending tools such as scenario analysis. S&P Global Ratings believes that these recommendations will bring environmental performance into the mainstream as an investment and credit consideration.

Toward A Plan For Mobilizing Climate Finance

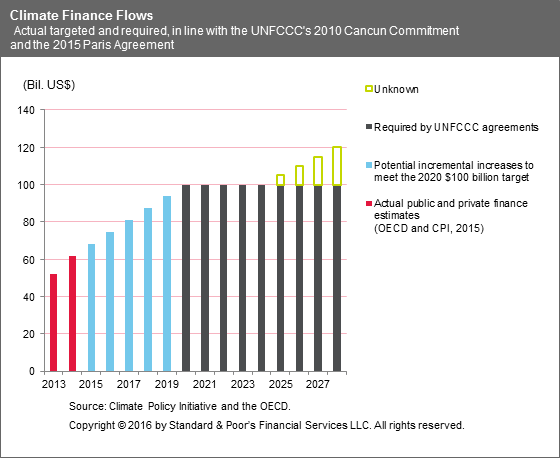

In 2010, the UN formalized an agreement to increase climate finance flows to $100 billion per year by 2020 from developed to developing countries for climate change adaptation and mitigation. COP 21 allowed for the continuation of the $100 billion target figure to 2025, with agreement that the parties will seek a more ambitious funding level for the next time period—that is, after 2025. COP22 needs to yield a finalized plan for mobilizing this $100 billion, which can come from public or private sources, in particular for striking a balance between adaptation and mitigation finance, as called for by the Paris Agreement.

The Green Climate Fund (GCF) was developed as a financial mechanism for the $100 billion target and currently has achieved pledges of $10.3 billion. Of this, the fund aims to disburse $2.5 billion this year, of which $1.17 billion has been approved. However, the GCF has faced questions because it has been slow to get off the ground, and has received criticism regarding governance and transparency. There are additional concerns that the GCF could reroute financing that might otherwise have found its way to other more established climate funds.

The OECD released an initial « roadmap » for climate finance on Oct. 17, which provides clarity about the status of current funding and outlines a possible route to mobilizing the $100 billion.

This exercise is made more complex because no single widely accepted definition of what constitutes « climate finance » exists. However, this is one point that COP22 is expected to review in order to keep a constructive discussion going.

COP22 also needs to work toward finalizing rules for reporting on climate finance initiatives, which would include disclosing both the finance provided, intended contributions, and finance required and received (in developing countries).

Renewable energy investment

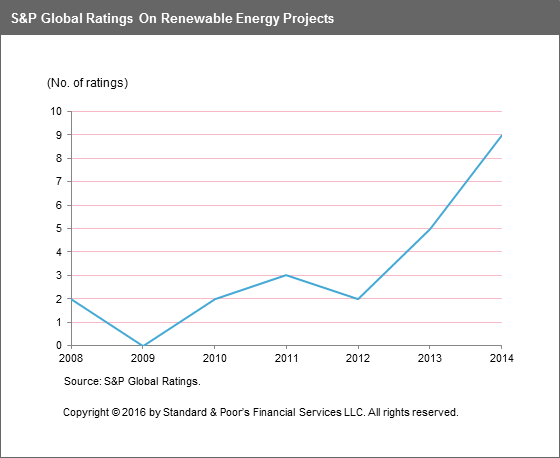

One aspect that is closely related to climate finance is investment in renewable energy, which is significant since the energy sector contributes most to global emissions. These figures look at global investment whereas the $100 billion climate finance figures above focus on flows to developing countries (mostly from developed countries). Overall, global energy investment (both renewable and fossil fuel combined) fell in 2015 to $1.8 trillion, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), a decrease of 8% in real terms from 2014, mostly due to a reduction in upstream oil and gas investment. However, investment in the electricity sector actually rose considerably to $690 billion, mostly because of renewables and network infrastructure. For the first time renewables (excluding large hydro) made up more than 50% (53.6%) of the gigawatt capacity of all technologies installed in 2015, which is a considerable milestone and most likely the sign of things to come. This fits with trends observed by S&P Global Rating’s infrastructure practice which has seen renewable energy project ratings increase steadily over the six-year period to 2014 (see chart 2). The low-carbon generation capacity that came online in 2015 was more than growth in global power demand, which explains why the average carbon intensity of generation is falling: Renewable capacity is beginning to replace some fossil fuel capacity. The carbon intensity of generation fell to 420 kilograms of carbon dioxide per megawatt-hour last year according to the IEA, but this is still insufficient to meet the target of « well below 2 degrees » as set out in the Paris Agreement.

Energy efficiency investment also increased even though energy prices fell. S&P Global Ratings believes this could be a sign that emissions reductions policies are taking effect, and that wholesale price signals are starting to play less of a role in driving investment decisions. The IEA believes that as much as 95% of power generation investment relies on vertical integration, long-term contracts, and price regulation. New forms of investment under innovative, consumer-led spending business models such as corporate buying of renewable power and distributed renewable energy for households and businesses also contributed $50 billion to investment figures in 2015.

Despite these positive figures in 2015, the picture in 2016 is looking less optimistic. Total investment in renewable energy is predicted to fall from 2015’s record of $348.5 billion, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF). Investment figures for the first three-quarters of the year were down approximately 20%, 20%, and 40% on their equivalent quarters in 2015. This is problematic as BNEF’s 2 degree pathway indicates that investment figures need to stay broadly in line with the 2015 record. One reason behind this decrease is that technology costs are falling; the same capacity can now be bought for less. However, other factors are weighing in such as China’s slowdown and the five-year extension of the U.S. Production Tax Credit for wind and the Investment Tax Credit for solar–meaning investors are not rushing to push deals through before the end of the initiative.

As well as acknowledging the renewed vigor required in renewable energy investment, S&P Global Ratings believes that fossil fuel infrastructure presents a looming risk, as we outline below in the next section. This is particularly relevant in regions where investment in fossil fuel infrastructure remains strong, such as India.

Green Infrastructure Investment: Significant Scaling Up Required

Instead of a gradual increase in investment in green infrastructure and decline in carbon-intensive infrastructure, much more may be needed. Research from Oxford University’s Sustainable Finance Program shows that if current operational energy infrastructure and planned additional energy infrastructure investment is made and operated to the end of its normal economic life, we won’t be able to build any more fossil fuel infrastructure after 2017 if we are to meet the 2-degree target.

Last month Lord Nicolas Stern and the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate estimated that $80 trillion-$90 trillion in infrastructure investments are required over next 15 years, which works out to between $5.3 trillion and $6 trillion on average per year. The key drivers of this requirement are:

- Higher growth rates and therefore increasing infrastructure demand in developing economies;

- Rapid urbanization, creating pressure on city expansion and development, which currently stands at about 50% of the population (about 7 billion) and is expected to rise to 70% by 2050 (more than 9 billion); and

- Aging infrastructure in advanced economies, which will need to be replaced or refurbished.

Global annual infrastructure investment stood at $3.4 trillion in 2014, so this figure would need to increase by at least 56% to reach the lower end of the $5.3 trillion needed on average per year. To put this in perspective, annual infrastructure investment has increased by $1 trillion over the decade to 2014.

S&P Global Ratings believes this demonstrates the need for a significant scaling up of infrastructure investment, and underlines the growing concern about stranded assets (assets that have suffered from unanticipated or premature write-downs, devaluations or conversion to liabilities). According to Oxford University, if policymakers are serious about reaching the Paris Agreement’s targets, all electricity infrastructure investment from next year onward will need to be green. Serious questions may be raised about the long-term viability of brown investment as regulation starts to tighten so that countries can reach their NDCs. New fossil fuel investment beyond that allowed in a 2-degree scenario would mean the early retirement of some fossil fuel capacity, meaning asset write-downs. The alternative option would be installation of carbon capture and storage technologies. However, these technologies are not yet widely commercially viable and can depend on access to a location having specific geological features.

S&P Global Ratings believes there is one big hurdle to investment in sustainable infrastructure: the initial increased upfront cost of most kinds of sustainable infrastructure, which the New Climate Economy estimates to be about $4.1 trillion in addition to the $80 trillion-$90 trillion required over the next 15 years. However, over the lifetime of these assets, the costs are generally offset by energy and resource savings, or resilience to extreme weather.

From Politics To Action

The world has made remarkable progress over the past 12 months that might have been almost unimaginable this time last year. The Paris Agreement came into force on Nov. 4, reassuring business and the financial markets that potential political turbulence is unlikely to easily derail the global climate agenda. However, it is no time for complacency because as the numbers show, serious political and financial commitments are needed to meet COP21’s goals and avoid the catastrophic impacts that climate change could bring. In our view, the ultimate success of the Paris Agreement hinges on the COP22 talks commencing over the next two weeks in Marrakech. It is time for governments and the private sector alike to start accelerating toward the green destination set in Paris.

Related Criteria And Research

- Proposal For A Green Bond Evaluation Tool, Sept. 2, 2016

- Paris Agreement–A New Dawn For Tackling Climate Change, Or More Of The Same, Jan. 18, 2016

- Climate Change–Building A Framework For The Future, Nov. 13 2015

- How Environmental And Climate Risks Factor Into Global Corporate Ratings, Oct. 21, 2015

- Standard & Poor’s Approach To Rating Renewable Energy Project Finance Transactions, April 20, 2015

Related External Research

- World Energy Investment 2016, International Energy Agency, 2016

- Climate Finance in 2013-14 and the USD 100 billion goal, Climate Policy Initiative and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, October 2015

- The ‘2°C capital stock’ for electricity generation: Committed cumulative carbon emissions from the electricity generation sector and the transition to a green economy, Institute for New Economic Thinking at the Oxford Martin School and the Smith School for Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford, March 2016

- The Role Of The Climate Investment Funds In Meeting Investment Needs, The Climate Policy Initiative, June 2016

- Better Growth, Better Climate, The New Climate Economy, 2014

- Climate Finance A Year After Paris: Driving Politics Into Action - 9 janvier 2017

Commentaires récents