Why should the question of gender equality be a priority in Europe, where women enjoy equal civil and political rights to men and equal access to education, primary rights that are not guaranteed to women everywhere in the world? Because, as this article shows, gender inequalities can take different forms and facets and outcomes can be very different ex-post from the ex-ante desiderata of a society. Macroeconomic data on women’s participation in the economic life of European countries suggest that gender inequalities entail significant economic costs that justify – beyond ethical reasons – placing gender parity at the centre of the debate.

Female participation to the workforce is very heterogeneous among European countries

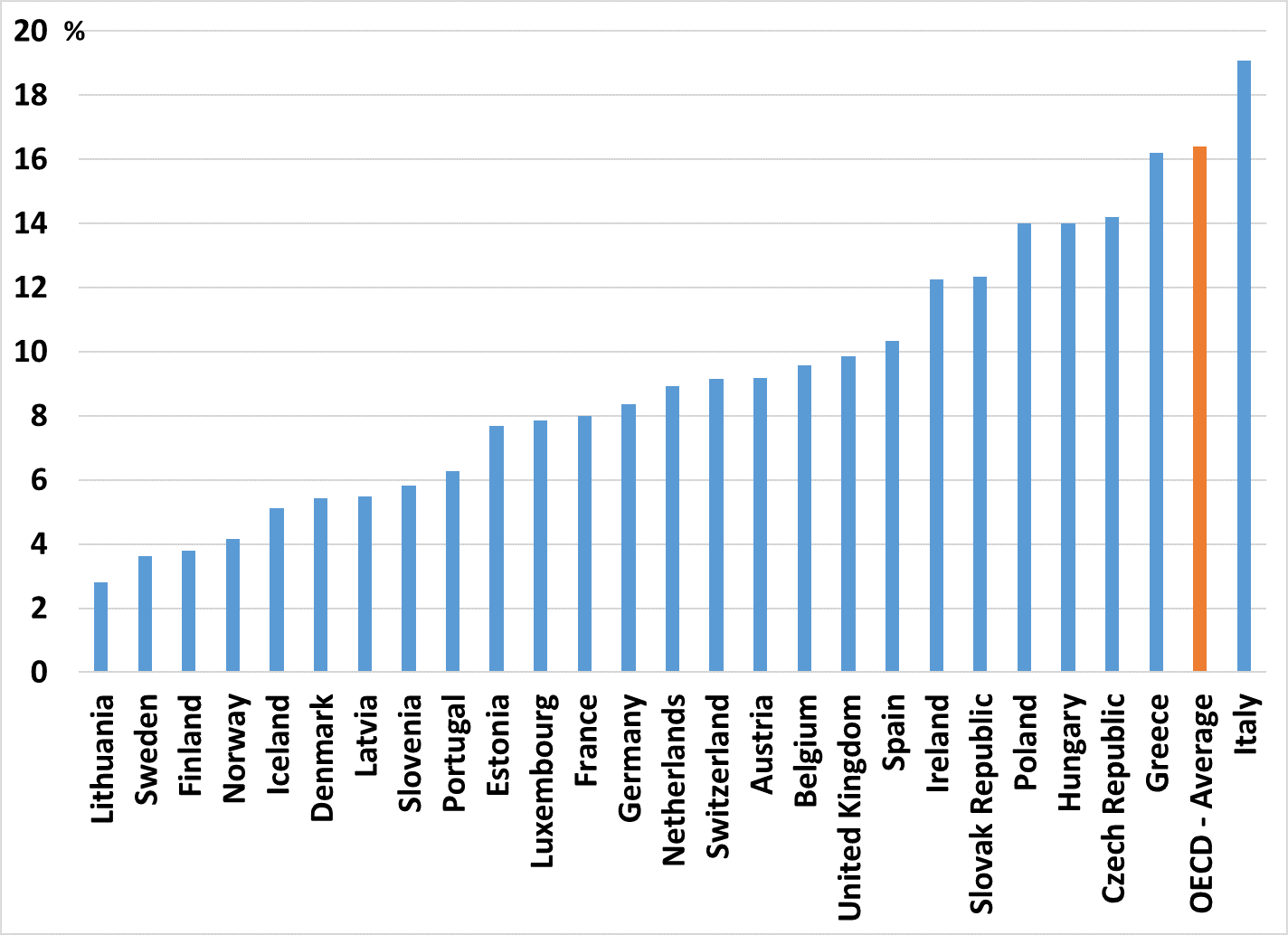

At macroeconomic level, figures for advanced economies speak for themselves: on average, the labour force participation rate of women is 16.4 percentage points lower than men in OECD countries (chart 1). This average mask a wide variety of situations across countries, which is particularly striking in Europe. On one side of the spectrum, there are Nordic and Baltic countries where the gap in labour force participation between men and women remains moderate (below or close to 5 percentage points), on the other side of the spectrum Southern and Central Eastern countries, where this gap is well above 10 percentage points. Italy appears as the black sheep in Europe with a gap of 19 percentage points as of 2017 according to OECD data. Gaps tend to increase even further when part-time jobs are taken into account, a factor that further exacerbates gender inequalities.

Chart 1: Gaps (male – female) in Labour Force Participation rates

Source: OECD 2017 data (age group 15-64) and author’s calculations.

The gains from gender parity can be potentially huge

We can think of these gaps as hidden resources in the economy that have not yet been allowed to express their potential. The fact that societies are depriving themselves of some of their available talents has an undeniable impact on their economic performance. A crucial ingredient of the recipe for higher growth would then be the implementation of structural reforms to increase the labour force participation rate of women, especially in those countries where the gap is widest. This major challenge has been properly identified by policy-makers – G20 Leaders for instance committed to reduce the gender labour force participation gap by 25% by 2025 in order to “contribute to stronger and more inclusive growth” – but progress has been slim so far.

Examples of policies going into this direction are those that make easier the access to finance and support for women-led businesses, favour employment opportunities and skills for women, improve social services, such as child-care and elderly care, and allow a better gender balance in parental and domestic tasks, such as shared parental leaves and teleworking. An increase in the share of women economically active in society would result into higher productivity and thus higher potential growth, especially in those countries that are more in need. Finally yet importantly, these reforms in the European Union and euro area may deliver as a by-product another desirable outcome, higher economic convergence among member states.

The potential positive and significant economic impact from a more gender-equal society is consistent with that found by the economic literature in recent years, both at macroeconomic and microeconomic level (see also Sestieri and Zignago (2019), for a review). To cite just two examples, Ostry et al. (2018) show that gender parity would be beneficial for productivity growth and lead to economic gains that go beyond simply increasing the labour supply, for instance by modifying the choice of educational pathways for both sexes and by changing social norms on the roles of women and men in society. Christiansen et al. (2016) found a positive correlation between gender diversity in senior positions and financial performance for a sample of two million European non-financial corporations. This correlation is significantly stronger in sectors that employ more women, as well as in knowledge-intensive and technology-intensive ones, which require the increased creativity and critical thinking that diversity can provide.

On average, European women work for free for about two months per year

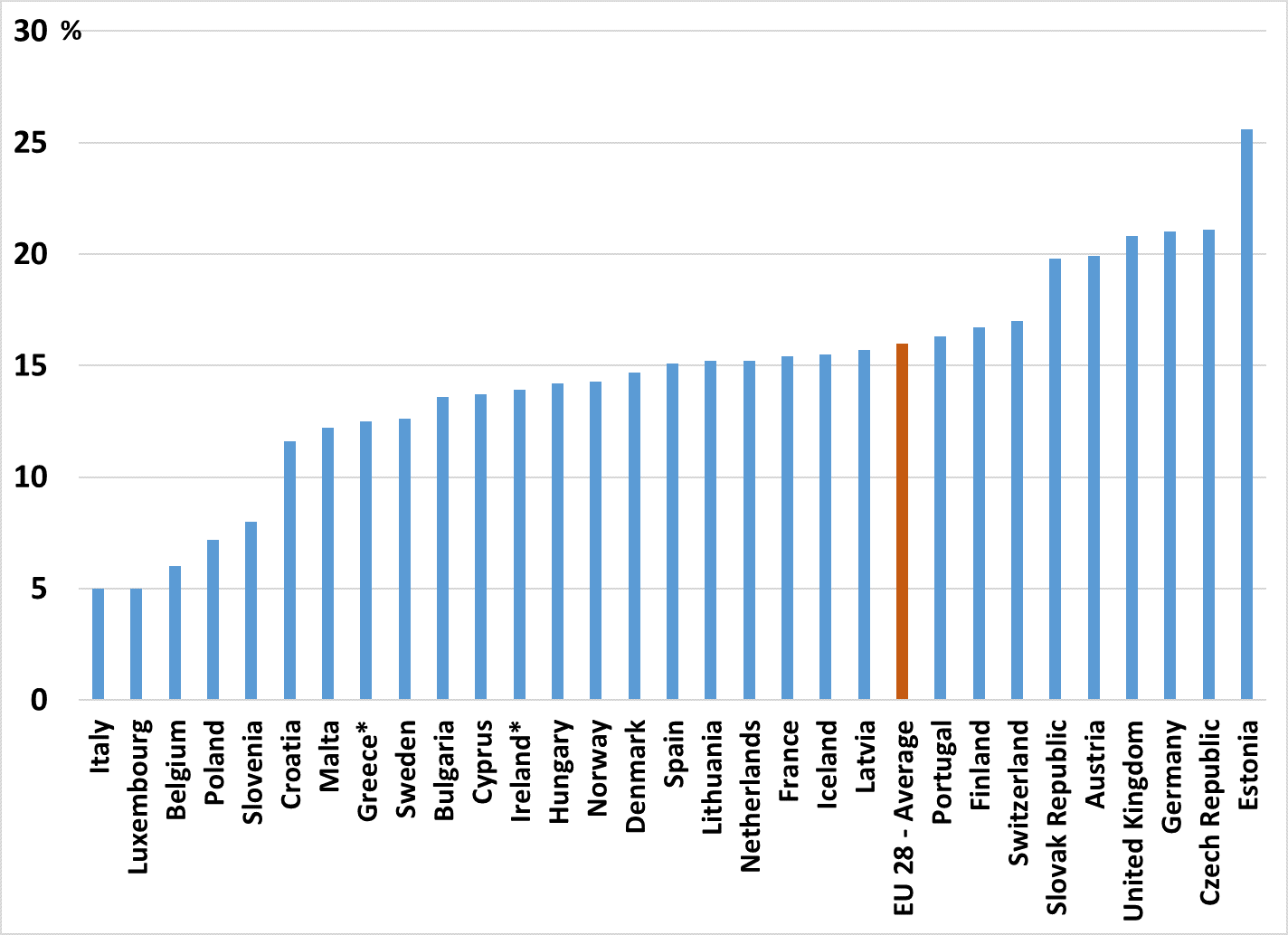

There is another dimension of gender inequality, which is less visible to the naked eye. Not only women participate less in the economic life, but when they are employed, they earn on average less than men. According to Eurostat data, the average gender pay gap in the European Union is about 16% in 2017, and reaches a peak of 20% or more in some countries, including some unsuspected ones, such as Germany, Austria and the United Kingdom (chart 2). In other words, on average in Europe women work for free for about two months per year, while men are paid for 365 days.

Chart 2: The unadjusted gender pay gap

Source: Eurostat 2017 data. 2014 data for Greece and Ireland (*). Difference between average gross hourly earnings of male and female employees, as % of male gross earnings, computed for firms with 10 or more employees. This measure is called “unadjusted” because it does not take into account other characteristics (sector of activity, age, occupation, etc.) of male and female employees.

This reality, which is ethically unacceptable, has also economic consequences in terms of lower aggregate consumption and tax revenues, to name just two. In order for these gaps to disappear, a change in the culture must go hand in hand with concrete actions, such as imposing economic sanctions to firms where such inequalities persist. This is for instance the rationale of a new law approved by the French Parliament in 2018 to tackle the still high French gender wage gap (about 15%). A common European reflection to support an Equal Pay Act would certainly be welcome.

Central bank governance: the last bastion of male power?

A well-known phenomenon, the so-called « glass ceiling », is that women in many sectors have trouble in accessing higher job positions. One striking example is the underrepresentation of women in central bank governance worldwide, and particularly in Europe (see also Istrefi and Sestieri (2018)). Not everybody knows perhaps that there is actually no single woman chairing a national central bank out of the 28 European Union countries, while figures for Deputy Governors in the EU stagnate at around 20% since 2012, according to the European Institute for Gender Equality. In this respect, central banks do much worse than governments and parliaments, where parity or at least increased feminisation is making progress. The recent appointment of Mrs Lagarde as President of the European Central Bank, whose mandate starts in November 2019, is definitely a good news but should not give room to complacency[1].

Europe can only benefit from pursuing and enforcing policies aiming at gender parity

To conclude, gender inequalities entail significant costs for society that justify placing them at the centre of the economic debate. If our sophisticated national and European institutions have not been able to make significant progresses on these issues so far, it is because it is mainly a cultural problem. If we want things to change, we must give ourselves the means to do it by putting in place a system that foster gender parity at all levels of the society and set it as a top priority in the years to come. The role of public policies is indeed to shape cultural habits and social evolutions.

Mots-clés : Gender diversity – labor force participation – pay gap – Europe.

References

Christiansen, Lone Engbo & Huidan Huidan Lin & Joana Pereira & Petia Topalova & Rima Turk, “Gender Diversity in Senior Positions and Firm Performance; Evidence from Europe” (2016), IMF Working Papers 16/50.

Istrefi, Klodiana & Giulia Sestieri, “Central banking at the top: it’s a man’s world” (2018), Banque de France Blog.

Ostry, Jonathan David & Jorge Alvarez & Raphael A Espinoza & Chris Papageorgiou; “Economic Gains From Gender Inclusion : New Mechanisms, New Evidence” (2018), IMF Staff Discussion Notes No. 18/06.

Sestieri, Giulia & Soledad Zignago, “The economic impact of gender inequalities” (2019), Banque de France Blog.

[1] NDLR : lire à ce sujet l’article de Klodiana Istrefi publié dans variances.eu le 2 octobre 2019

- On the economics costs of gender inequality in Europe - 28 octobre 2019

Commentaires récents