Suite à une étude réalisée par des économistes de Rutgers University aux US, cet article de CityLab analyse la hausse fulgurante du terrain immobilier à Manhattan : en 2014 la totalité du terrain « constructible » était estimé autour de 1,7 trillions de dollars US, plus que le PIB du Canada. L’étude identifie plusieurs facteurs, Wall Street et ses primes, le boom de l’écosystème Tech, l’effet Google et l’attrait de capitaux étrangers.

Un article sélectionné par Frédéric Smadja (2000), le correspondant de Variances.eu aux Etats-Unis : l’article, rédigé par Richard Florida, a été précédemment publié dans « CityLab».

A new study traces the astonishing increase in the value of Manhattan’s land since 1950.

Our biggest urban problems today—growing inequality, rampant gentrification, housing unaffordability, and increasing segregation—all have roots in the staggering cost of urban land. Nowhere is this as true as in Manhattan, home to some of the world’s most valuable real estate.While the city has long been a global capital, the value of its land has traveled an uneven path. Back in 1626, the Dutchman Peter Minuit “bought” Manhattan, “the island of many hills,” from the Lenape people for $24 worth of trinkets. Since then, most of the hills for which it was named have been flattened, some new land has been created, and the island has become one of the priciest places in the world. Determining just how valuable that land is, however, is a tricky proposition.A new study by economists from Rutgers University tackles this question with a methodology that not only provides an estimate for the current value of the land, but also its growth in value over time.

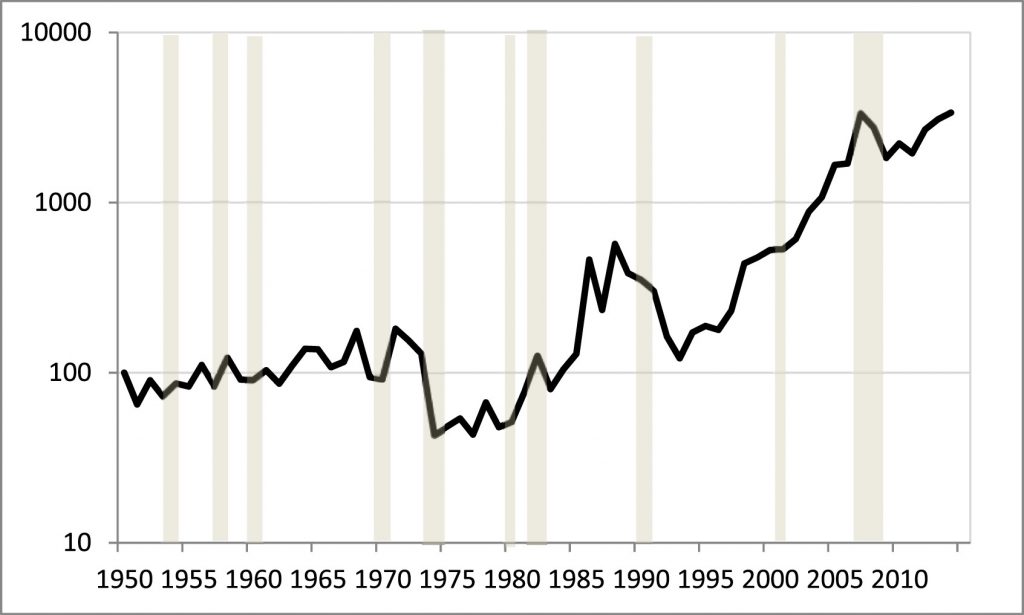

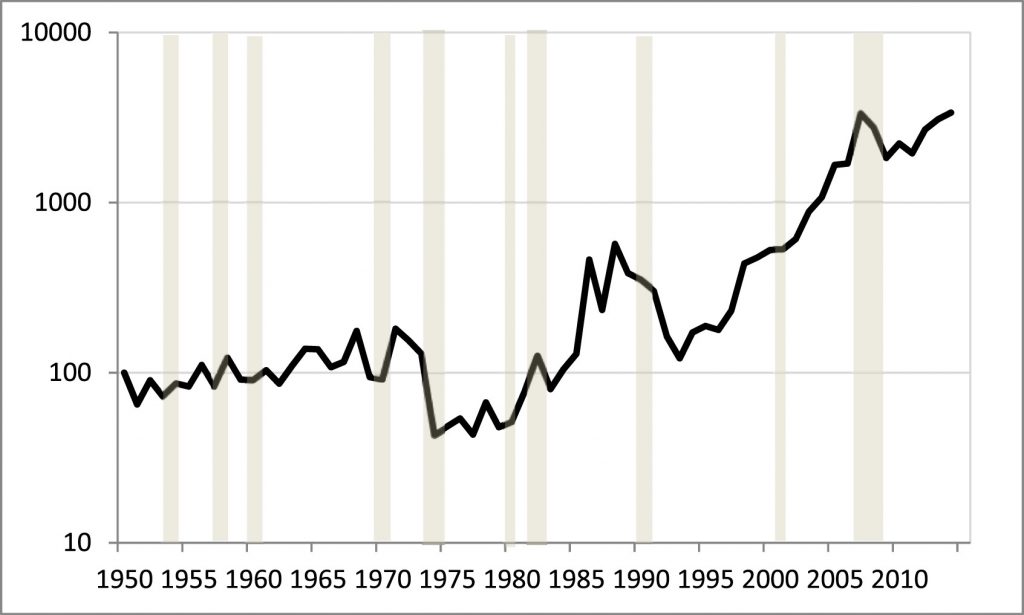

The forthcoming paper in Regional Science and Urban Economics estimates that in 2014, the developable land in Manhattan—excluding parks, roads, and highways—was worth between $1.54 and $1.95 trillion, for an average of $1.74 trillion. That figure is significantly larger than the combined market capitalization of the world’s three largest corporations that year, and similar to the economic output of Canada, the world’s 10th-largest economy.The researchers (Jason Barr, Fred Smith, and Sayali Kulkarni) arrived at that number by analyzing the prices of vacant parcels of land in Manhattan. This enabled them to avoid the problem of disentangling the land value from the value of the structure that sits on top of it. Using data on all vacant land transactions from 1950 to the first quarter of 2015, they built a land value index that represents the change in Manhattan’s land value over time, adjusted for inflation.The graph below, from the study, charts the land value index over those 65 years. (The Y axis is compressed to show the massive scale of the index in a reasonably-sized graph.) Over that time, the value of Manhattan land grew at an annual rate of 5.5 percent, adjusted for inflation. But, as the graph shows—and as anyone familiar with New York City knows—the rise of Manhattan’s land value has been far from linear. Indeed, the study identifies three major real estate cycles in Manhattan.

Manhattan Land Value Index, 1950-2014

(Barr et al./Regional Science and Urban Economics)

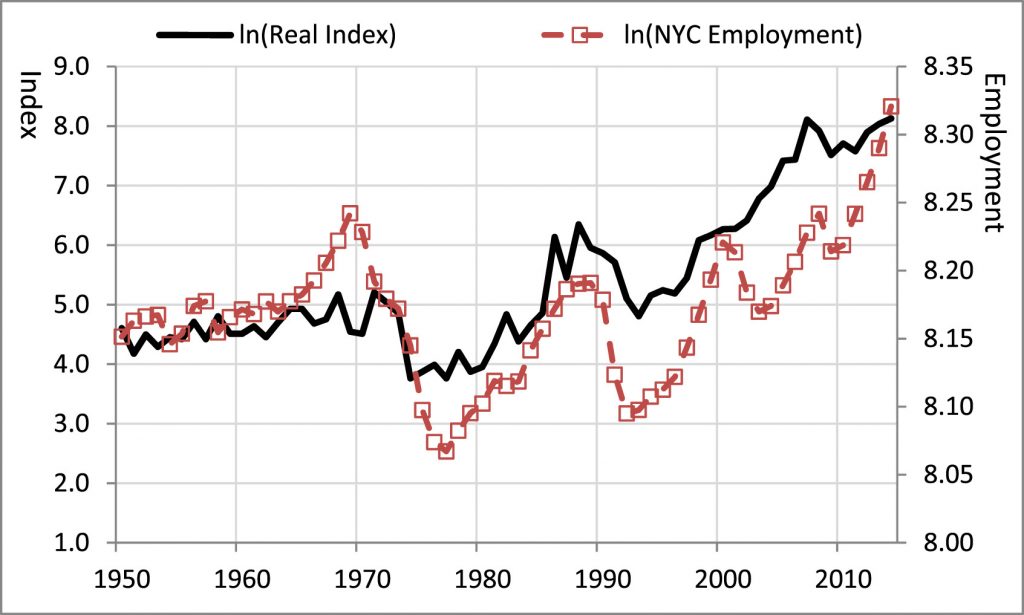

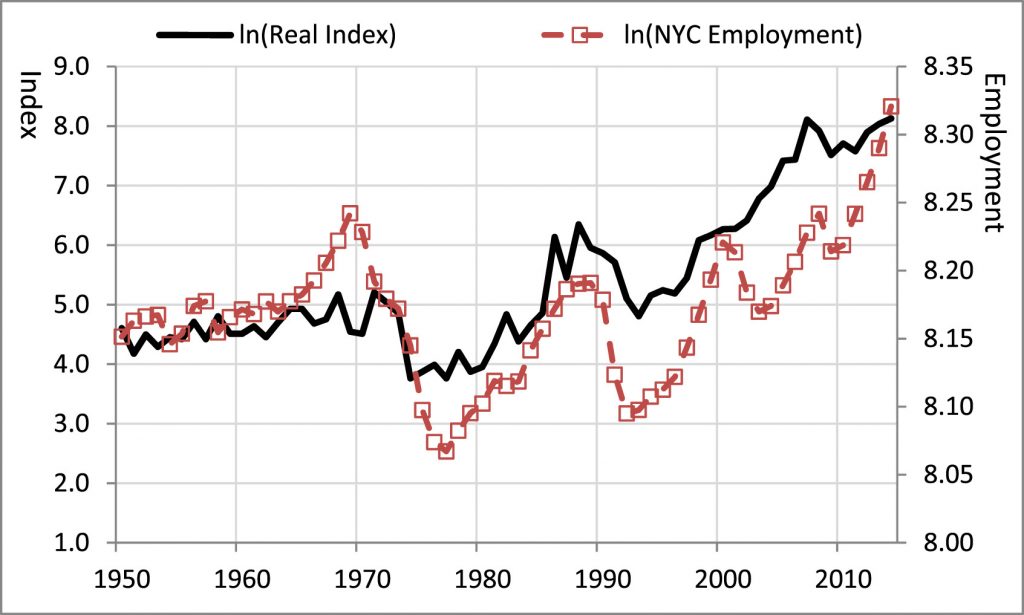

The recent surge is often attributed to the outsize compensation and bonuses on Wall Street. But the study does not find any significant connection between the performance of the S&P 500 and the land value index.

What seems to matter more is the overall employment rate in New York City. This would, in turn, seem to be a proxy for the recent back-to-the-city movement of jobs and people. Over the past two or three decades, Manhattan has seen increased demand for its land as affluent people and large corporate headquarters moved back into the city, as well as startups and more established tech companies.Today, Manhattan trails only San Francisco as a location for VC-backed high-tech startups. Google has become one of the largest landowners in Lower Manhattan. And, of course, the past decade or so has seen a tremendous influx of foreign capital into Manhattan real estate, which is now viewed as a safe vehicle for storing capital, much like gold.

Manhattan Land Value Index and Total NYC Employment

(Barr et al./Regional Science and Urban Economics)

For New Yorkers, and those who aspire to be New Yorkers, the study provides empirical data for what you already know: Manhattan real estate is expensive, and it has gotten even more so in recent years.

Perhaps the 1960s and 1970s, the period so romanticized by New Yorkers and others as an era of tremendous creativity fueled by cheap real estate, was the exception. With increasing demand from businesses and people for limited space, it has now become prohibitively expensive for all but the affluent to live in Manhattan, contributing to the sorting by class and geography that is dividing our cities and our nation.

Les derniers articles par From US

(tout voir)

Commentaires récents